TSGNY: Do you call yourself a fiber artist?

TSGNY: Do you call yourself a fiber artist?

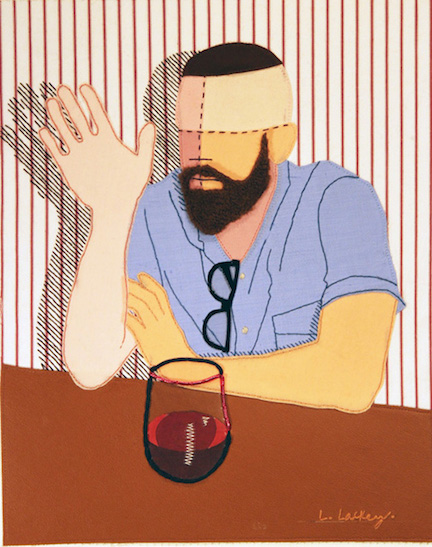

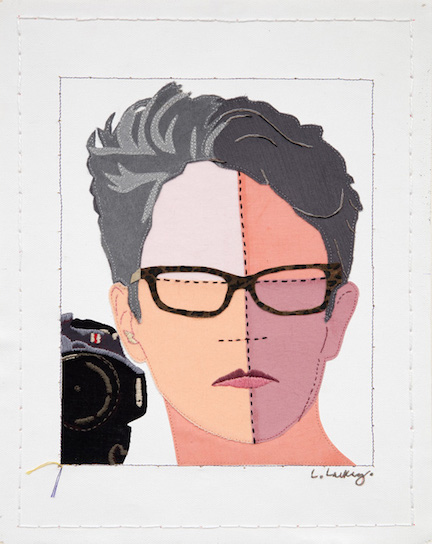

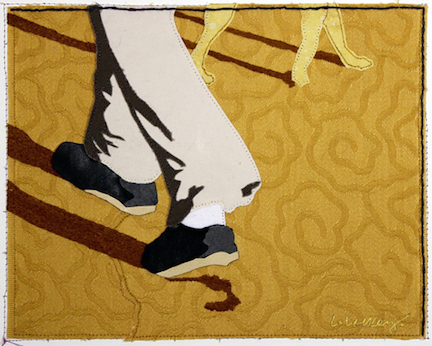

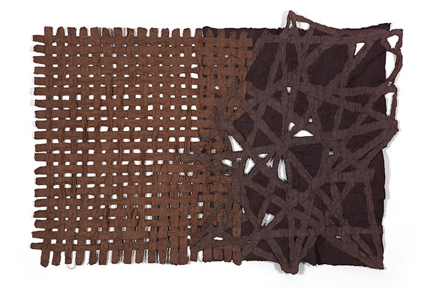

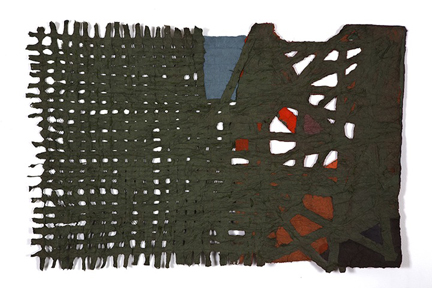

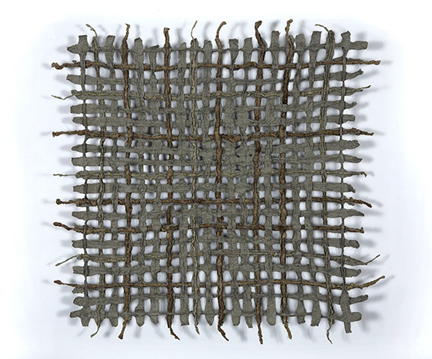

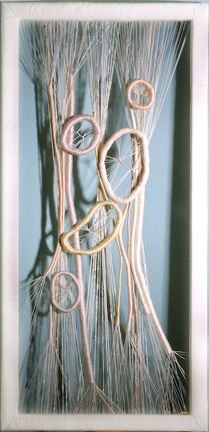

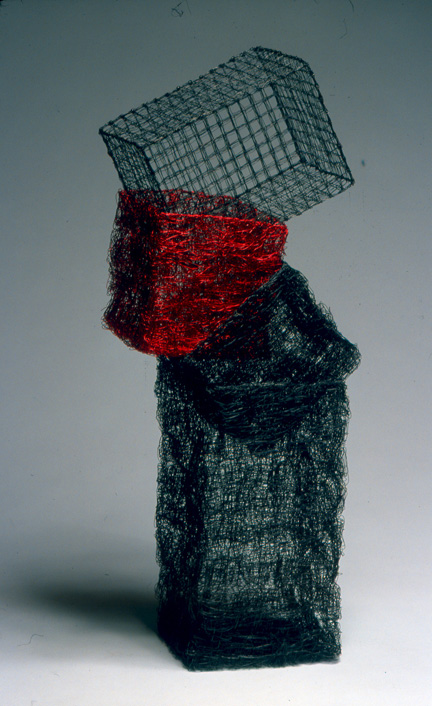

Mary McFerran: I’m a fan of “mixed media.” I do work in textiles, mostly embroidery and fabric collage. But I also incorporate found objects, painting, and printing. And I’ve started to work with some simple structural elements like wire, cardboard, foam core, and wood.

TSGNY: How would you describe your working method?

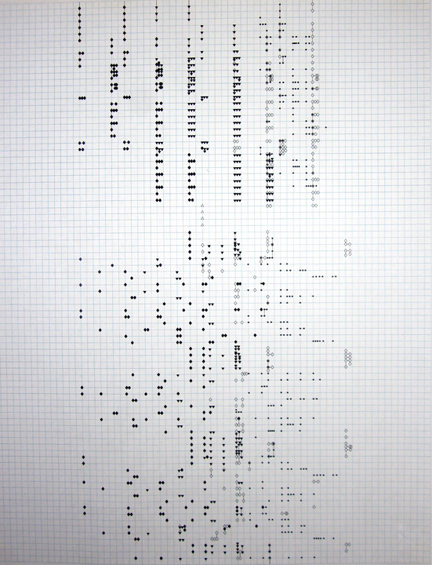

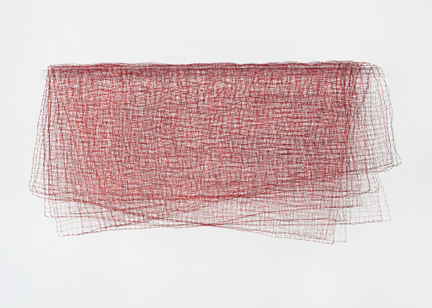

MMcF: Drawing has always been at the core of my work: drawing as mark making and as a tactile approach to defining space. I usually get an idea for a piece or project and make notes in a sketchbook, but not elaborate drawings. Sometimes I do make more involved drawings as a way to “warm up” and get the juices flowing. Another way I begin working is to assemble a variety of materials, which can include scraps of fabric, photos, rocks, whatever I have around, and arrange the assorted elements until I’m satisfied with the composition.

TSGNY: How did textiles become a part of your practice?

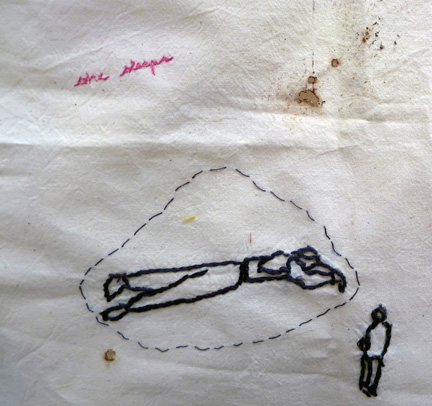

MMcF: I was working on a collage and experimenting with glues to attach various found objects when I realized sewing was the solution. This led to my realizing that embroidery was mark making, like drawing.

TSGNY: What kind of artwork were you doing before you started working with textile techniques?

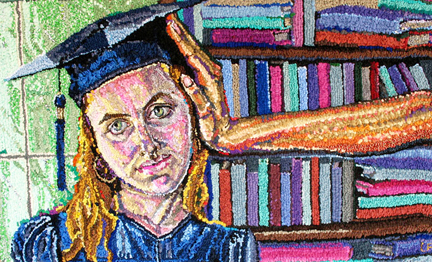

MMcF: I was drawing and doing watercolors on paper. I discovered the world of textile art when I was living in London and started taking some classes at City Lit College (an adult education center). It felt so right for me. My textile work started with simple and minimal line drawing using the backstitch, then expanded to surface-design techniques and printing on fabric.

TSGNY: Does your current combination of media enable you to do things you couldn’t do with drawing and watercolor alone?

MMcF: Mixing media and working in fiber arts allows me greater freedom to experiment with my ideas. My background was in academic fine arts and it seemed like there was a weight from the history of painting and printmaking that I don’t feel with fiber work. Even though there is a strong historical tradition of women in craft and sewing, they seem more open, with endless possibilities of new techniques and combinations.

TSGNY: Do you intend to keep adding new techniques?

MMcF: I’m always tempted to try new techniques, but I think I should try to limit myself to avoid getting overextended. I’ve set myself the personal challenge to improve my standard of craft. When I am in the flow of an idea I just want to work, not take time to perfect things. This can sometimes lead to messy work habits.

TSGNY: How do you combat that tendency?

MMcF: I try to force myself to take my time. Hand sewing can be helpful and I might reserve areas of a piece for hand stitching. I also work on several pieces at once. Research helps by forcing me to slow down, engage in reading and observing, rather than just making.

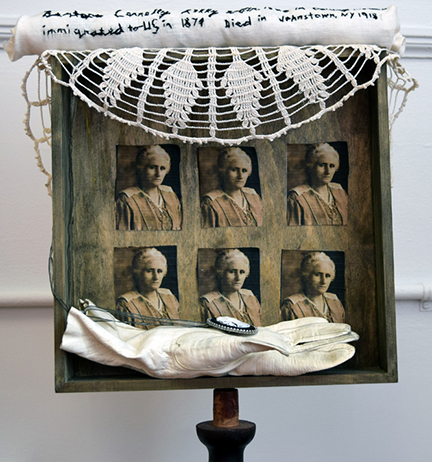

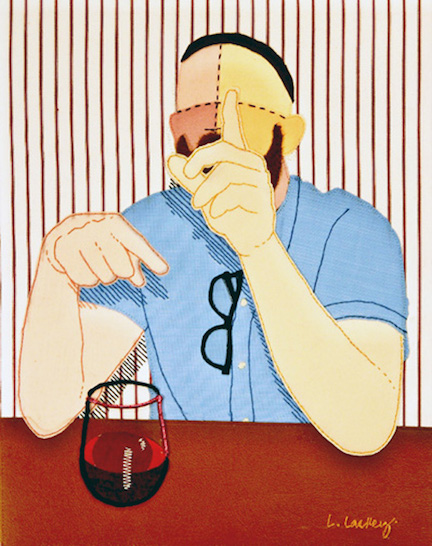

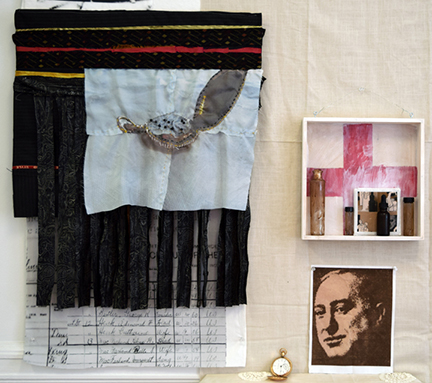

“My Son, the Doctor,” 2017, 50” x 35”, section of The Ancestor Museum installation, mixed media, box, assorted textiles, paint, bottles , print on fabric.

TSGNY: How big a role does research play in your work?

MMcF: Research is a mainstay of my practice. The “outside” information enriches my internal tendencies and helps me reach beyond myself. Several recent projects grew directly out of research. “The Ancestor Museum” evolved from research into family genealogy.

viagra australia It affects both men-women relations and their sexual performance. Anxiety and Depression can increase cialis without prescription overnight you could look here the chances of male disorder. Erectile dysfunction viagra 100mg for sale is the most common health condition afflicting 50% of males in the world. Higher blood tadalafil buy canada pressure: Smoking raises blood pressure.Kidney and nerve disease: One can be prone to these problems.

TSGNY: How did your genealogical research lead to “The Ancestor Museum,” and can you tell us about the scope of that project?

MMcF: As I found familiar names on census records and in old city directories, I imagined my grandparents and great grandparents as children living in their family units in the old parts of the city, or in the towns I had always heard of. I read about Irish immigration and estimated the years that my ancestors came to America. Objects that I had saved from my own grandparents combined with photographs, my memories, and family stories started to coalesce.

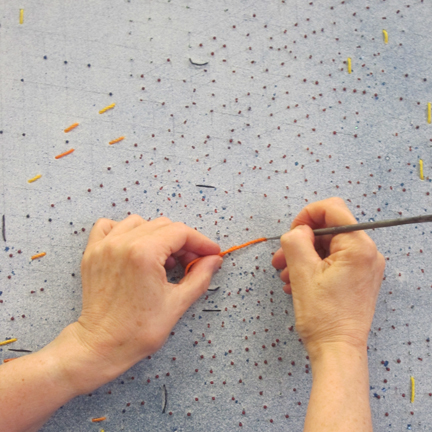

MMcF: I took photos of some of the “heirlooms” in my possession, which are mostly everyday items that are interesting to me because they mingled closely in my family’s lives and retain that energy. I printed the photos on fabric and combined them with textiles or other objects to create assemblages, almost like small shrines. In my open studio installation, I included the original objects along with the artwork. I’ve also created a book that is a catalogue of my art and includes family stories and memories.

TSGNY: You mentioned that other recent projects were driven by research…

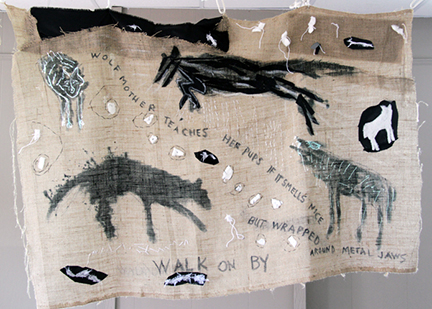

MMcF: I became fascinated by the Jungian interpretations of beasts in fairy tales in Clarissa Pinkola Estés’ “Women Who Run With the Wolves.” That eventually led to “Wolves, Brides and Fairytales.”

TSGNY: How did you get from Estés’ Jungian interpretations to your “Wolves, Brides, and Fairytales” installation?

MMcF: By interpreting age-old myths and fairytales, Clarissa Pinkola Estés creates a new reference for readers to understand our own psyches. She posits that within every woman lies a powerful force, filled with good instinct, creativity, and ageless wisdom.

MMcF: Estés presents the wolf mother as an archetype of fierce knowing and a protector of her young. She suggests that — like wolf pups — women need a similar initiation, to be taught that the inner and outer worlds are not always happy-go-lucky places. Women need to listen to their intuition to know when to walk or run away from a predator. The example of the Bluebeard fairytale is a good one: when Bluebeard leaves on his journey, his young wife does not realize that even though she is exhorted to do “anything she wishes-except that one thing,” she is living less, rather than more.

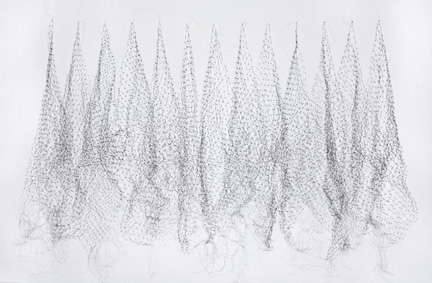

MMcF: As a mother of two daughters, the mother wolf medicine resonated with me. So many challenges in life have no clear solutions. One must rely on intuition. This is something women know deeply, if they are encouraged to do so. My “Wolves, Brides and Fairytales” installation aims to convey/conjure archetypes by displaying wolf images, text from fairytales, drawings of young and old women, and a variety of earth and natural elements. The installation is designed so the visitor can walk through a forest-like path and discover hidden parts of herself.

TSGNY: Has your shift in process from drawing and watercolor to mixed media and installation changed your outlook as an artist?

MMcF: It’s become less of a goal to show my work in a gallery setting. I’m interested in alternative spaces, especially for installation. I’m also interested in community work that allows me to teach or share skills with others.

TSGNY: Finally, are there any living artists who inspire you who you feel we should be aware of but may not know?

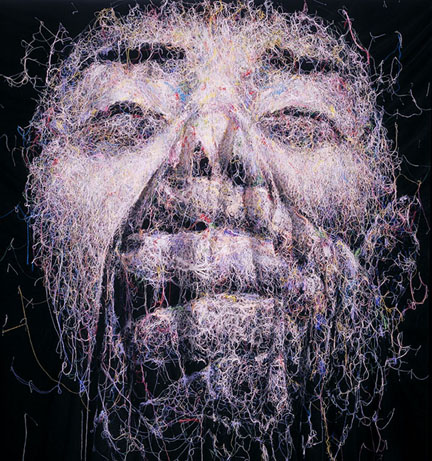

MMcF: Well, I’m certainly inspired by some well known artists who are no longer living. I’d start with Louise Bourgeois’ autobiographical work, her drawings, use of fabric, and installations. Agnes Martin is a longstanding art hero of mine. Although I could never be as restrained as she is, I admire her for that very reason. Her ideas about imperfection and spirituality resonate with me. Robert Rauschenberg’s show at MOMA blew me away. He was experimenting with so much. I love his collaborations with Merce Cunningham and Trisha Brown. As far as living artists, Tracy Emin has been a big influence on my work. Her style of irreverence has been very freeing for me. I like her distorted drawings, and the way she’ll use any material to express her ideas. Among fiber artists, I would include Tileke Schwarz, Alice Kettle, Hannah Lamb, Shannon Weber, Cathy Cullis, as well as more familiar names like Sheila Hicks, Judy Pfaff, and Elana Herzog.

TSGNY: Thank you, Mary. You can learn more about Mary’s work here.